It matters little whether we regard the point of view

of the savage…or that of the astronomer,

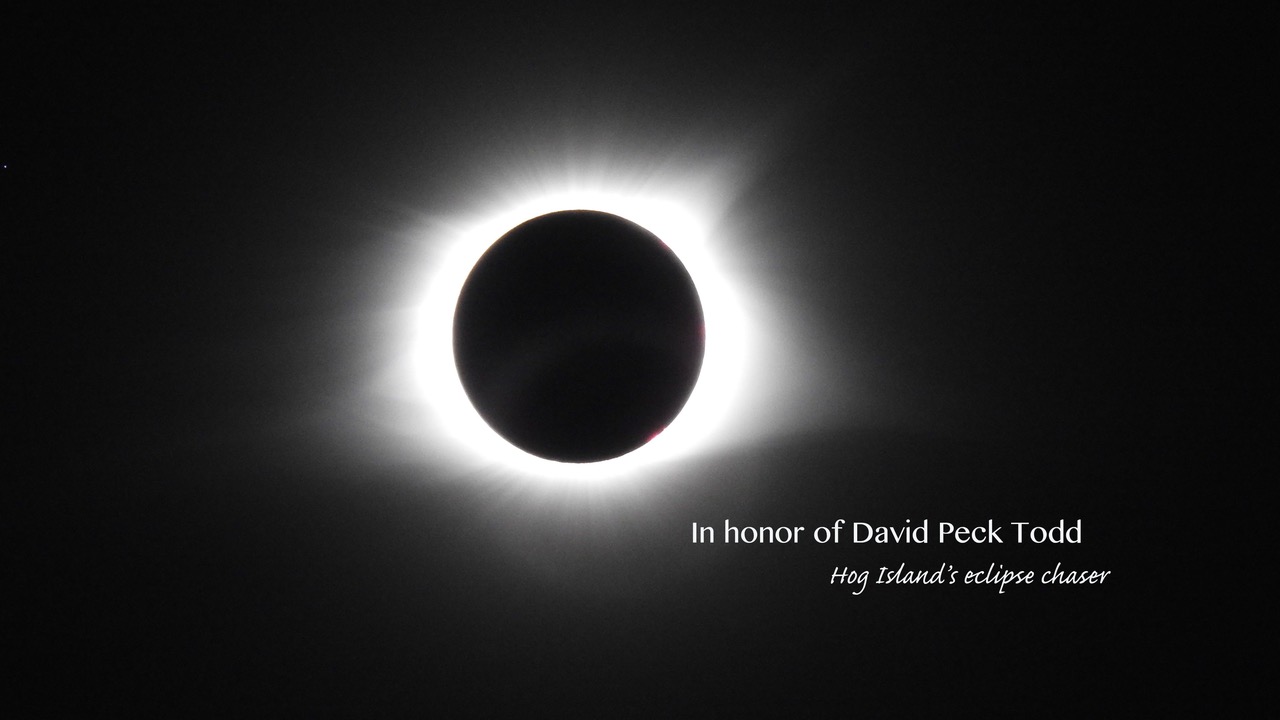

the total solar eclipse is a most imposing natural phenomenon.

Mabel Loomis Todd

Total Eclipses of the Sun (1894)

If you and yours were some of the millions of Americans who traveled mucho miles to personally witness the celestially rare experience of a total solar eclipse last 21 August, you have something uniquely in common with Hog Island history.

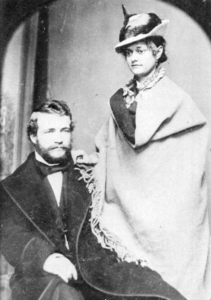

And if you are an Audubon camper, you no doubt remember the part of the opening session narrative as retold from Millicent Bingham’s decades of addressing campers about her mother, Mabel Loomis Todd, who is still blessed there regularly as both primary ‘savior of Hog Island’ and the first editor of the Emily Dickinson canon of poetry and letters. Somewhere in that storytelling you might also remember mention of Millicent’s father, David Peck Todd, who is usually simply noted as chief astronomer at Amherst College a century ago and notorious for being, among other things, a global total solar eclipse chaser.

As a college student, David Todd cut his eclipse teeth by observations not of Earth, but of Jupiter. His meticulous observations and record keeping of eclipses of Jovian moons, and subsequent publication of that data, caught the attention of famed American astronomer Simon Newcomb who gave Todd his first job as a special assistant and ‘calculator’ at the Naval Observatory in Washington D.C. A few years later, Todd would take the astronomy job at Amherst where he and his new wife and little girl would make their home which proved fertile ground for the development of three very illustrious and successful careers.

Getting to totality, of course, is the first order of business before witnessing this unique and ‘most imposing natural phenomenon.’ My wife and I braved expected heavy interstate traffic through Ohio and Kentucky to get to Tennessee for our experience. We heard on the news that those 60,000 folks who joined us at Triple Creek Park in Gallatin, thirty miles north of Nashville, came from 39 states and 17 countries, including two busses of Japanese observers. During David Todd’s era of observations, one can only imagine the added degree of difficulty required to get not only expedition members to the precise path of totality, but also crates of sensitive optical equipment, often over miles of difficult terrain. All for a mere few quick minutes of totality.

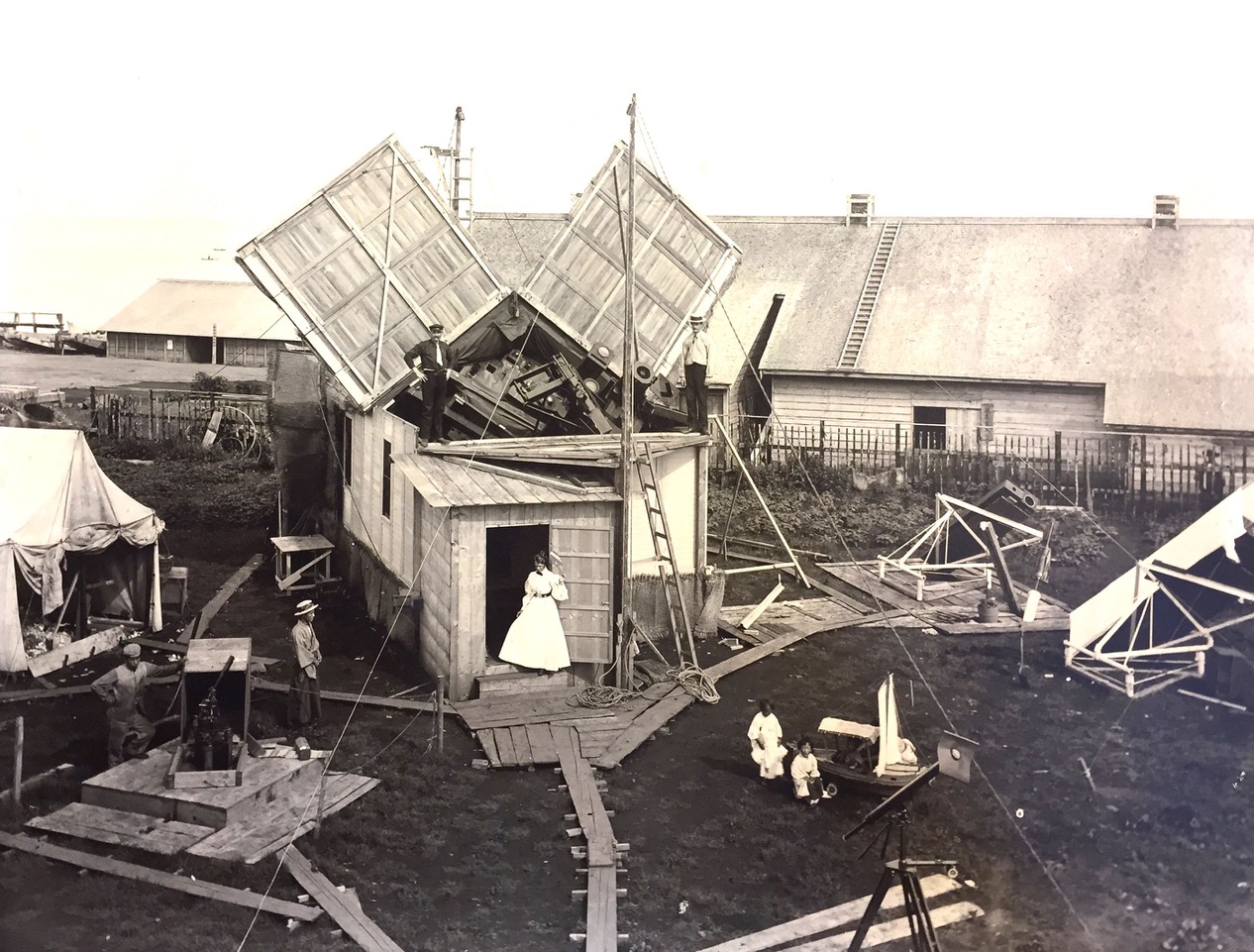

As if expedition life wasn’t hard enough, often on the outskirts of civilization, there was never a promise of clear skies. Twice, in both 1887 and 1896, David and Mabel and observation teams sailed to Japan to record the sun’s corona using an innovative photographic camera system designed by Todd. It took eight months of difficult sailing and overland travel to record on wet photographic plates what solar science could only view at totality. And it was cloudy. Both times. So if you had clear skies like we did at Gallatin, you did a whole lot better than many of Todd’s dozen or so expedition teams. Such makes it easier to understand Millicent’s family anecdote that the only thing her father ever admitted to really upsetting him was clouds at totality. And if you know much about Todd family history, that really was saying something.

In part because catching totality under clear skies was inherently risky, David Todd assembled broadly based scientific teams to join his expeditions. The thinking was that even if all the money and effort spent on photographing the sun’s corona resulted in failure, other scientific natural history data, like flora and fauna study and collections, would result in the team bringing something of value home. Keep in mind, too, that the nation of Japan the Todds personally experienced was not yet fifty years removed from Commodore Perry’s abrupt appearance in 1854 to negotiate a trade treaty. Japan was a nation of mystery to Americans who were eager to learn more about the secretive and exotic Land of the Rising Sun. Which is another place in history where Mabel Loomis Todd fits right in.

Mabel Todd did not accompany David on all of his expeditions, but she didn’t miss many. Following both trips to Japan, she published articles in national publications with broad readerships, including The Atlantic Monthly and The Century Magazine. Whereas Dr. Todd and his team collected scientific data, Mabel focused on cultural issues in articles titled ‘An Ascent of Fuji the Peerless,’ ‘In Quest of a Shadow: An Astronomical Experience in Japan,’ and ‘In Aino-Land.’ American readers were hungry to hear more about the island nation most would never have the opportunity to travel to.

Mabel Todd produced a few full-length books from her global travels with her husband. Total Eclipses of the Sun (1894) had a mostly scientific bent but was aimed at explaining astronomical phenomena to laypeople while Tripoli the Mysterious (1912) focused on north African culture, another topic with broad interest among American readers at the time. A third book, though, Corona and Coronet (1898), offered a theme that resounded deeply in me as we awaited totality in Tennessee. Mrs. Todd wrote about the camaraderie that developed among the expedition team sailing on the Coronet on the long and difficult trek from New England to Japan. David even mentions that bonding by dedicating one of his own published works to the Coronet crew.

I surely don’t mean to imply the thousands of us who gathered at Triple Creek Park became best of friends like the Coronet crew did, but there was a palpable sense of community among us. I felt it, as did my wife, my brother, his wife, and the dozen or so strangers who found shade under the same tree we did. We had gathered to witness a once-in-a-lifetime event, and that elevated place we found ourselves was not lost on us. I did not hear one hostile word from anybody I saw all day. One family under our tree gave a tee shirt away to a guy who they only knew by first name who had gone to look for one, but found they were sold out. Another family offered surplus catered lunches they brought along to a younger family with kids just because the young ones looked hungry. I went over and tapped the younger dad on the shoulder and said, ‘Kind of like the loaves and the fishes, eh?’ He grinned and nodded while another woman who heard me looked up a bit startled and said, ‘I wonder if that’s how the miracle did work? People just brought out food to share when they knew their neighbors were hungry.’ How could I disagree? Maybe spectacular celestial events just bring out the best in us.

I’ve been a fan of Mabel and David Todd for years, even before I first heard their story about Hog Island. Being able to witness, first hand, that same spectacular yet elusive prize David spent a career trying to capture makes them feel even more like kin. It’s not just the aura of being on that special island in Muscongus Bay that they protected over a century ago, but now the etched-in-consciousness singular event of experiencing the sun and moon in their unique dance that produces the only time human beings can see the corona and planets together at midday. Now we have another commonality that assures our place in the fold of Nature’s People.

***

If you enjoy hearing stories about legendary Hog Island personalities, be on the lookout for my book, Nature’s People: The Hog Island story from Mabel Loomis Todd to Audubon. I’ve been at it for a while, and it’s a whole lot closer to publication, but there’s still fathoms to go. Look for an announcement at fohi.org when it’s available.

Images: Opening image of totality (Tom Schaefer, 21 August 2017, Gallatin TN) David and Mabel Todd (Todd-Bingham Family Papers at Yale University archive) ‘Amherst Station, Esachi, Japan 1896’ (Todd-Bingham Family Papers at Yale University archive) Note Mabel Loomis Todd standing in the doorway.

Tom Schaefer

tom@earthspeaks.org

Dayton, Ohio

August 2017